July 14, 2004

Press Articles :: Photographer's Forum

by Grace Califano Schaub

|

In 1986, photographer David Michael Kennedy and his family traded in the fast-paced, urban hurly-burly of the Big Apple for the dusty, laidback western town of Cerrillos, New Mexico. They were in search of a less stressful lifestyle. Kennedy had lived in Manhattan for 18 years and, during that time, had established himself as a leading commercial photographer. His work received a great deal of attention from art directors, and he won numerous awards, including a CLIO. His celebrity and editorial portraits were regularly featured in Penthouse, Spin and Omni magazines, to name a few. He worked extensively for the music and entertainment industries, including CBS Records, photographing their leading recording artists. These stunning portraits and images were featured on posters and album covers. His decision to leave New York, and head out west, wasn't made lightly. He felt he had reached a crossroads in his life, and wanted to take his photography in another direction. Kennedy describes it like this: "I felt as though I had reached a plateau. I was in a very comfortable place, but I had to either climb to another level, or slide down, and I knew I didn't want to do either." Kennedy says if he had stayed in New York, the next step up meant moving up to a bigger, more elaborate studio, hiring more assistants, getting an agent and taking on twice' as many assignments as before. But that wasn't what he wanted. |

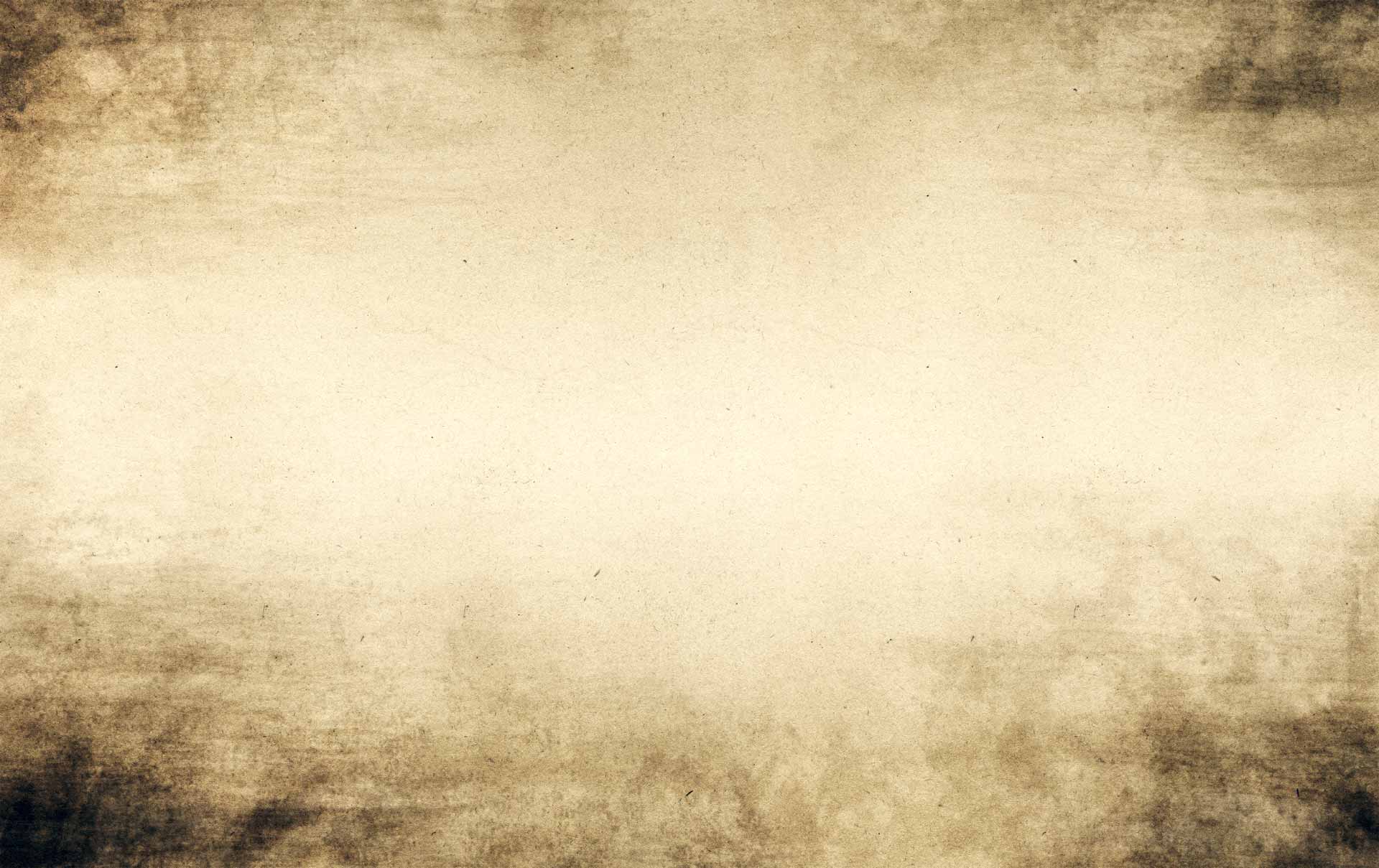

Kennedy with Jumping Bull |

Kennedy believes that by showing where the dancers come from, he reveals the courage, hope, strength and spirituality of these people. "I'm out to show what they have to deal with on a day- to-day basis," he says, "and how strong and resilient a people they are.

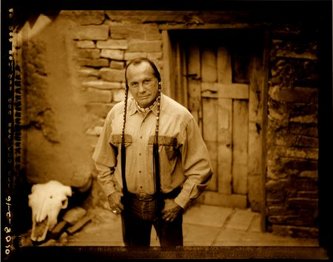

Sundancer, August 2003, palladium print

Ghostdancer, Lakota Nation Palladium Print

|

"I already had a very busy work schedule and was stressed out and tired. But I always strived to do my best work, whatever the conditions were, because my photography has always meant a lot to me. I realized that what was more important to me was not to get more clients or a bigger and better studio, but to create better pictures that were closer to the heart of my photography." When he finally made the decision to leave, he left himself a bit of a cushion, knowing that he was sacrificing a large chunk of money to make the switch. "I left with enough assignments to last a year," recalls Kennedy, "and it took about a year until more came my way. "Most of the work, at that time," he says, "was location work and involved traveling. I was still doing editorial work and shooting album covers, but not really doing anything to keep that part of the business flourishing. I had no agent and I didn't seek out new work. Whatever assignment came my way, I strived to do the best work I could in that particular situation." He clearly didn't want to continue the hectic pace he had set for himself in New York out in New Mexico. Other matters awaited him there, some of which were set in motion in New York. "In those first few years in New Mexico, I started doing my own work. I had no gallery representing my work. Assignments were slow, but I would take the location work when it came my way." And although there were some hard times financially, Kennedy added on a positive note that his living expenses were certainly much lower in Cerrillos than in Manhattan. Cerrillos is a small, dusty western town about halfway between Santa Fe and Albuquerque. When you first step into Cerrillos, it feels like you're back in the history of the Old West, with its one main street, old adobe saloon and general store. Kennedy has since moved closer to Santa Fe, but while in Cerrillos he became very much a part of that community, even volunteering for the local fire department. After six years he became the deputy chief."I had more time, and I started doing my own work. The first thing I got into was the landscape. It took me one or two years to understand what I wanted to do photographically in the landscape." Kennedy's landscapes are powerful, and his cloud images reminiscent of Stieglitz with a western and therefore grander flair. By 1987, Santa Fe Light Works, a new photography gallery, had opened in Santa Fe. Kennedy brought in a portfolio of work, which led to an exhibition. "Something happened after that first show in Santa Fe," says Kennedy. "I started getting a lot of publicity. The New Mexican -Santa Fe's newspaper -had my face on the front page, which embarrassed me. The story line read something like 'Big Celebrity Photographer from New York Moves to Small New Mexican Town, Gives Up Big Career to Live in 100 Year-Old Adobe.' And next, the Albuquerque Journal published an article on my work, and suddenly my name was all over town." The Andrew Smith Gallery in Santa Fe has been representing Kennedy ever since,

|

Windbreak, Wyoming, December I995, palladium print |

|

GEAR AND TECHNIQUE Kennedy's work is done with medium format and large format cameras. His most recent work is with a large format camera and Polaroid 4xS positive/negative film. He uses a handheld 4x5 camera that he says looks like an early Cambo and has mounted a wide-angle, 6Smm lens that yields falloff on the edges. It is very much like a point-and-shoot box camera, he says, or like photographing with a pinhole camera. "This camera, and this way of photographing, is forcing me not to be a perfectionist," Kennedy says. "The film is flimsy and scratches easily, and these glitches are part of that medium. One element of the process for me is learning how to accept the defects, and just let it happen. I don't demand the same perfection that I do in my palladium prints. But the silver prints do have their own inherent beauty. Also, I've been working with a Holga and a Zero pinhole camera, and there is a certain amount of serendipity involved. In some cases, I don't know what I'm really shooting, and that sort of appeals to me. It's about letting go. "The 4x5 camera I am working with now has a Schneider lens and works better for me." But whatever gear Kennedy uses.. he sees it all as an exhilarating experience, a creative challenge to go outside the box and Push the creative envelope in new directions.

|

Grandma Curley, Coyote Canyon, New Mexico, July 2003, toned silver print |

|

NATIVE AMERICAN DANCERS Kennedy is perhaps most well known for his exquisite images of Native American dancers. The pictures have an intimate appeal and spiritual presence that immediately strikes the viewer as something more than a document of a dance. There are good reasons for this. The images surely involve his unique eye and his respect for the people and their culture. But what comes through most in these, and his other photographs, is his personal involvement with the people he photographs and his sense of communion and liaison between the photographer and the person who perhaps might later look at his images. "When the person sitting for a His involvement with the Native American dancers, and sub- sequent essays and individual photographs, began, oddly enough, because of his work with Penthouse magazine. The magazine's publisher, Bob Guccione, gave Kennedy the assignment to photograph Leonard Pelletier, one of the members of the American Indian Movement, who is serving two life sentences in prison. Said Kennedy, "The involvement with Pelletier at Leavenworth, where I did that story, renewed my spiritual aware- ness and involvement. It showed me that I could do many things with my photography beyond making money. I was just ready to hear all that, I suppose, because ever since I was a kid I felt a kin- ship to Native American culture:" The portfolios of Native American dancers strike a chord in people who might never have heard of Leonard Pelletier or know what the Sun Dance is. While his technique of photographing from a low angle with a medium format camera creates an inti- mate yet respectful pose, there is something beyond point of view that comes through in each image. His portfolio is enhanced even more by his use of palladium printing techniques. All the photographs of the dancers were made away from public areas so as not to offend any tribe members who might not understand the purpose or permissions given Kennedy. "But it was not removing the people from the experience -- in fact, they all had a say in what I did and how I did it, and every time I sell one of the prints a percentage of the money goes back to the tribes. "My first portfolio of dancers was made with the northern New Mexico Pueblo people, and then I began to photograph the Lakota people, who .live mostly around the Black Hills .of South Dakota." One project Kennedy wished to complete was photographing the Sun Dance, a very special ceremony for the Lakota. "I had attend- ed the dance many times but had not photographed it," he relates. "The Lakota Dance Portfolio, as this project came to be called, required the inclusion of the Sun Dance, but I always knew it would take me time to get permission to do that photography and time to get it right. It took me four years. "I always go directly to the traditional elders, the medicine men and the other leaders of the old way for permission, and for guidance on whom to photograph. I believe that respect. must be given; and in that way it will be returned." THE PINE RIDGE SERIESKennedy's latest portfolio of black-and-white images, Pine Ridge, looks behind the scenes at the people depicted in his earlier dancer portfolios. The Dancers portfolios were made up of elegant, unique, limited edition, warm-toned palladium prints. The Pine Ridge series gives a starker impression and is made up of black-and-white silver images. It is more documentary in approach, showing the often hard reality of Native American life. "I felt as though had reached a plateau.

|

Russell Means, San Jose, New Mexico, March 2003, tone silver print |

|

Kennedy believes that by showing where the dancers come from, he reveals the courage, hope, strength and spirituality of these people. "I'm out to show what they have to deal with on a day-to-day basis," he says, "and how strong and resilient a people they are. A picture of a trailer might look sad and depressing, but the people there still have time to honor their spirits with ceremonies and sweat lodges. As I look at these prints," says Kennedy, "I see these people as true survivors, and how they have endured. In a way, after doing the Dancers work I felt that I really wanted to photograph and share the other side of Native American life. It is a harsh land -it's not all regalia, ceremony and dancing. But despite the hardships, in front of the camera people become transformed and show what a proud people they truly are." Kennedy's prime concern when doing portraits is to uncover the uniqueness of the individual. He says, "All people have a special beauty, even when our culture says they don't. It is my goal to reveal the soul of each individual. My aim is for the viewer of my photographs to actually engage in a dialogue with the person photographed. When the person sitting for a portrait speaks to me with their eyes wide open to the inquiring camera, they create the possibility for a conversation with whoever may examine the photograph in the future. "I am thrilled by the possibility of creating a space in which the subject may reveal himself or herself in an intimate way. Often it's their only access to that other person who might see them only in a photograph. I believe that a lot of power exists in this interchange, and I am honored by the trust exhibited by both the subjects and viewers engaging in this silent dialogue." Although he is respected worldwide for his photography and the integrity and quality of his images, Kennedy's profound sense of the power of the photograph does not affect his picture of himself. "It surprises me that people know me," he says, "because I am just another photographer making pictures." Grace Califano Schaub is an artist and photographer who writes on photography and contemporary photographers. She teaches photography at The New School University in New York City, and has co-authored The Marshall's Handcoloring Guide and Gallery. Her own handcolored black and white photographs have been exhibited around the country. Her work is represented by the Variant Gallery in Taos, Mew Mexico. You can reach Grace at grace_schaub@hotmail.com

|

Waiting for White Bear, Porcupine, South Dakota, December 1996, palladium print

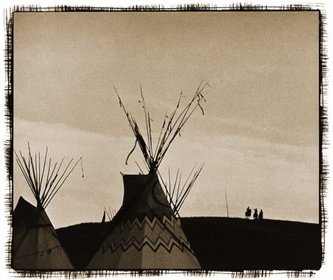

Don King N.Y.C. November 1983, palladium print

|