June 1, 2004

Press Articles :: Rangefinder Magazine

|

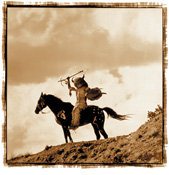

Profile: David Michael Kennedy by Peter Skinner |

| Reprinted from Rangefinder Magazine - June 2004 |

|

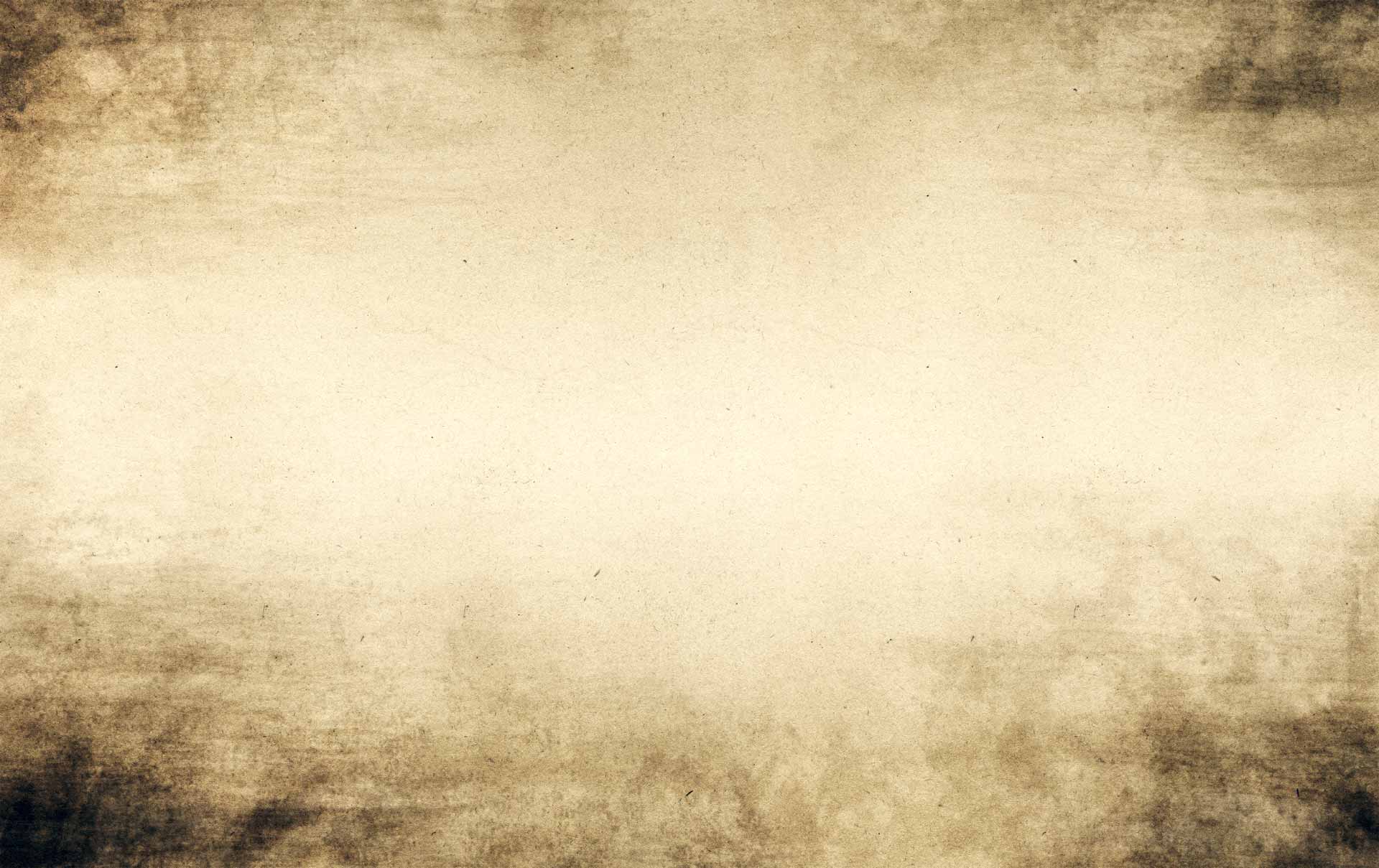

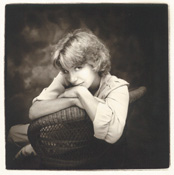

Santa Fe, New Mexico, photographer David Michael Kennedy is a firm believer that things, even what seem to be very bad things, happen for very good reasons. Perhaps that is why he can rationalize with remarkable aplomb why his house burning down about a year ago was just the impetus he needed to take his work in a new direction. And why he is as excited about his current documentary, slice-of-life environmental project on the Pine Ridge Reservation and beyond—shooting with a handheld 4x5 camera—as he has ever been in his whole career. And that includes his 18-year stint in New York City where he was at the top of his game specializing in the music industry. In essence, Kennedy is going through a rejuvenating experience that will culminate in a completely new collection of images, both portraits and landscapes that will further enhance his reputation as a challenge-seeker, risk-taker and fine art photographer. Kennedy, who from 1969–1987 was based in New York City and became one of the city’s leading advertising and music industry photographers, has for the past 15 years focused his energies and creativity on the native peoples of the West and the stark, dramatic landscapes of their environment. He is a master of palladium printing, a painstaking and demanding process that is ideally suited to the final presentation of the evocative and haunting images that now constitute much of his portfolio. While his primary subject matter for these last 15 years has been the culture of Native Americans, his principal goal has been to accurately and sensitively portray the spirit of that culture. In 1989, two years after moving to New Mexico, Kennedy photographed the American Indian activist Leonard Peltier in Leavenworth Penitentiary. Peltier’s allegedly illegal incarceration by the United States government affected Kennedy, and he was impressed by Peltier’s fortitude to withstand lifelong imprisonment and to spiritually escape from his confinement. Kennedy became determined that his photographs should aid Native American causes, and set about on a huge undertaking. He probably did not realize at the outset what he was getting himself into. The full scope and details of his work in his area can be seen at his web site.

“The politics involved in getting access to photograph these ceremonies was complicated beyond belief, and the production itself was huge. At times I felt like I was back in New York working on some million dollar advertising campaign. I wanted to keep these ceremonies visually alive but the pressure involved was intense. Most of the elders and medicine men and women understood and supported what I was doing, but others, usually younger people with bad attitudes about white people and life in general, didn’t. Some people didn’t like what I was doing, and they were in my face; others didn’t understand my motivation, and they were in my face; others thought I was exploiting the situation, and they were in my face. So, at times it was very stressful,” he says.

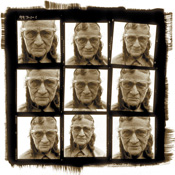

This was followed by working for seven years with the Lakota people, an undertaking that was completed only recently with coverage of the Sun Dance, an intense ritual that Kennedy gained permission to photograph only after going through an extraordinarily long political process. The images that Kennedy made of the Lakota dancers prior to the Sun Dance include Ghost Dancer, Coyote Dancer, Wolf Dancer, Dog Soldier and a series of powerful portraits of elders and dancers. The body of work is now complete with the Sun Dance photographs, but Kennedy says he still has to finalize his Lakota portfolio. It should be stressed that a portion of all proceeds goes back to the tribes. This is a commitment that Kennedy made from the outset and one that he has fulfilled throughout.

After 15 years of concentrating on these projects, Kennedy was ready for a change, even if he didn’t know it. The catalyst for change was the fire that destroyed most of his home—all the living area and everything within. Amazingly, the fire stopped at the walls to his studio and darkroom, thus saving most of his work and invaluable negatives. But that fire and the resultant moves from one location to another, all the while dealing with the contractor, have taught Kennedy patience. The fire also made him rethink what he was doing and why. “I was trying to preserve the visual side of these traditional ceremonies, and I thought I was doing Native Americans a favor. But then I realized I wasn’t presenting the whole, or real, story of what’s happening today with these people. When they are dressed for ceremonial events—with ornate, traditional costumes and feathers—it looks as if all is well with their world. In reality, there are a lot of problems such as poverty and substance abuse on the reservation, even among the dancers I have been photographing. Their lives are very hard. So, I decided to start a new project, more of a documentary thing—a slice of real life. And I am shooting it with positive/negative Type 55 Polaroid film using a handheld 4x5 camera,” he says. Coincidentally, at about the same time he was asked by California activist Russell Means to do a show and this dovetailed with the theme of his documentary project.

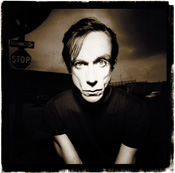

The camera he is using is something like the Sinar Handycam, and also similar to a camera assembled and used to great effect many years ago by Steve Salmieri. Kennedy found his camera while on a visit to New York and while it looks and functions like the Sinar camera, neither he nor any others have been able to identify its make. Regardless, fitted with a 65mm Schneider Super-Angulon lens it has proved ideal for Kennedy’s current project. And the camera has one other important benefit—the response it elicits from Kennedy’s subjects. “When you put a Nikon 35mm camera or Hasselblad in someone’s face there is a certain type of response from them, often not what you want. But when I pull out this weird looking large format camera and don’t mess around setting up a tripod, they immediately become curious and excited about being photographed with it. It’s working really well for what I am doing and the results are great,” he says.

Even though Kennedy’s new work is being produced with different techniques from his earlier images, they blend well together and have the distinctive David Michael Kennedy look. “I have always had a problem with words like ‘style,’ but when you see this new work, you can see it’s mine and has a similar feel to my other images. So, I guess you could say my style shows.” In a nutshell, Kennedy’s latest endeavors are triggering new enthusiasm, similar to the excitement he felt some 15 years ago when he first ventured to New Mexico from New York City. Growing up in Northern California (Eureka), Kennedy has country roots, and relocating to New Mexico was like coming home.

Photographers from the two factions viewed each other with something akin to contempt; today, the lines are more blurred with many photographers overlapping into both fields. Also, Kennedy’s New York credentials and a continuing flow of New York-based assignments, helped soften the landing into his new community where he not only gained acceptance but also is now a fixture, his work being sold through the prestigious Andrew Smith Gallery in Santa Fe. Kennedy admits he is far from a “techno freak.” (In fact, he still uses the original Hasselblad outfit be bought through a special time payment arrangement with Ken Hansen in New York back in 1971.) His work, fine art and commercial, is deeply rooted in the basics of the craft. Personal vision, visual problem solving, and craftsmanship in all aspects go far beyond the boundaries of technical stuff. And he willingly shares his vast knowledge through workshops, both his own and in programs with The Santa Fe Photographic Workshop.

The real keys to Kennedy’s success have been great talent and perseverance combined with unrestrained enthusiasm and excitement when new challenges present themselves or are initiated by the man himself. And while a setback such as your house being destroyed by fire might dampen most people’s enthusiasm, the flames which burned David Michael Kennedy’s home also were the catalyst to create a new body of work. And it won’t be long before the world will see what he has achieved with a handheld, weird looking 4x5 camera and Polaroid Type 55 film. His new show of about 60 pieces was scheduled to open at the 1st Street Gallery (www.1ststreetgallery.com), Boca Raton, Florida, from November 14 for a month to six weeks.

|

That he has compiled a superb portfolio of ceremonial dances and dancers and that his efforts have been acclaimed by his Native American subjects as well as outsiders, is a tribute as much to his diplomacy and perseverance as to his artistry.

That he has compiled a superb portfolio of ceremonial dances and dancers and that his efforts have been acclaimed by his Native American subjects as well as outsiders, is a tribute as much to his diplomacy and perseverance as to his artistry. Kennedy could’ve added that it was also time consuming. Initially, he worked with eight northern Pueblos in New Mexico, and over five to six years, he created an impressive body of photographs of ceremonies such as the Nambe Spear Dancers, Picuris Deer Dancer, San Juan Eagle Dancer (this image literally comes alive with the blurred movement of flying wings), Santa Clara Corn Dancer, Taos Hoop Dancer, Tesuque Buffalo Dancer and the Pojoaque Butterfly Dancer.

Kennedy could’ve added that it was also time consuming. Initially, he worked with eight northern Pueblos in New Mexico, and over five to six years, he created an impressive body of photographs of ceremonies such as the Nambe Spear Dancers, Picuris Deer Dancer, San Juan Eagle Dancer (this image literally comes alive with the blurred movement of flying wings), Santa Clara Corn Dancer, Taos Hoop Dancer, Tesuque Buffalo Dancer and the Pojoaque Butterfly Dancer.

Also, for this project Kennedy has reverted to silver printing (“I used to be a hell of a silver printer,” he says) instead of his long-standing favorite, platinum/palladium. This change has helped increase his productivity. He can now print three to four negatives a day, about 20 a week. “I was lucky to make two to three new images a week with the palladium process. This way I am becoming really productive and am putting together a huge body of work of silver prints,” he says. “And it’s exciting the hell out of me.”

Also, for this project Kennedy has reverted to silver printing (“I used to be a hell of a silver printer,” he says) instead of his long-standing favorite, platinum/palladium. This change has helped increase his productivity. He can now print three to four negatives a day, about 20 a week. “I was lucky to make two to three new images a week with the palladium process. This way I am becoming really productive and am putting together a huge body of work of silver prints,” he says. “And it’s exciting the hell out of me.” He was brimming with eagerness at photographing in a new environment. But there was some trepidation at venturing into fine art. At that time, he says, very strong lines separated fine art and commercial photography.

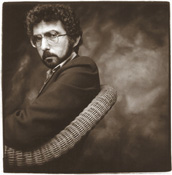

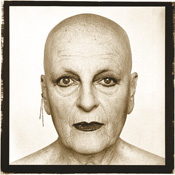

He was brimming with eagerness at photographing in a new environment. But there was some trepidation at venturing into fine art. At that time, he says, very strong lines separated fine art and commercial photography. Kennedy, who attended Brooks Institute of Photography and the New York Institute of Photography, first went to New York in the late ’60s to have back surgery. Following that, and short of money, he initiated his New York City career. For several years, he assisted still life specialist Randy Legname before venturing out in 1971 on his own freelance career, eventually becoming a leading light in the music industry, shooting numerous advertising campaigns and album covers, and along the way winning many awards. He was able to do that by initiating a series of editorial portraits of leading art directors, which led to their giving him a stream of ongoing work. The art director series, and his tribute to those who really supported his career, are featured on his web site. And the list of musicians he photographed range from Bob Dylan (who actually helped Kennedy set up all the lighting equipment rather than have Kennedy arrive with an entourage of assistants), Debbie Harry, Iggy Pop, Muddy Waters, Willie Nelson and Charlie Daniels.

Kennedy, who attended Brooks Institute of Photography and the New York Institute of Photography, first went to New York in the late ’60s to have back surgery. Following that, and short of money, he initiated his New York City career. For several years, he assisted still life specialist Randy Legname before venturing out in 1971 on his own freelance career, eventually becoming a leading light in the music industry, shooting numerous advertising campaigns and album covers, and along the way winning many awards. He was able to do that by initiating a series of editorial portraits of leading art directors, which led to their giving him a stream of ongoing work. The art director series, and his tribute to those who really supported his career, are featured on his web site. And the list of musicians he photographed range from Bob Dylan (who actually helped Kennedy set up all the lighting equipment rather than have Kennedy arrive with an entourage of assistants), Debbie Harry, Iggy Pop, Muddy Waters, Willie Nelson and Charlie Daniels.