February 9, 1988

Press Articles :: East Mountain Telegraph

|

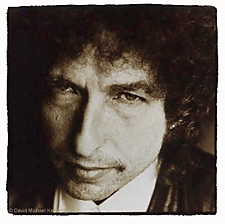

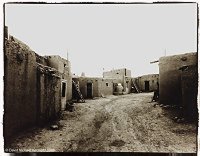

East Mountain Telegraph Volume 1, Number 3, February 9, 1988 I drove my junker into Cerrillos. Why, I asked myself as my car bumped over pot-holes, would a guy who photographed Bob Dylan move from Manhattan to dusty little Cerrillos? People hammered and painted away at old buildings on main street. The town, basking in sand-colored light, left me feeling peaceful and at ease. Cerrillos, one can't help but notice, is built to human scale. Stepping into David Michael Kennedy's house, I was immediately thrust into the craziness of his past. "Steve, I can't deal with that type of money. You know that's not my interest." He busily talked on the phone with Steve who, from the sound of their conversation, resided in New York City and was connected to $$$. "I bet our income dropped $200,000 this year when we moved here," David told me later. "But we wanted to move...." "For a better quality of life," Lucy, his wife, chimed in. Stepping from yellow-serene Cerrillos into city-madness was only a brief interlude. Kennedy can operate at both extremes. Since moving here seven months ago with Lucy and their 3 1/2- year-old son, Jesse, David has attained an amazing Cerillosesque calmness. It turns out his minauderie (French for trademark) for photographing famous people is based on "just being human." Among subjects done for advertising and record covers are Bob Dylan, Julian Lennon, Muddy Waters, Isaac Stem, Bruce Springsteen, George Carlin and on and on. To hear him talk almost gives you the feeling the world is a small community. Kind of like Cerrillos. |

|||||

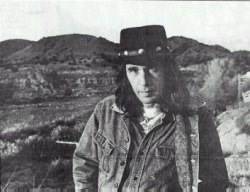

"I was never goal- or career-oriented except that I just wanted to take good photos," he told me while we sat at their kitchen table. "Like I didn't say, I want to do pictures of famous people, or I want to do advertising. I would just kind of meet people, and things would come out of those meetings." David Kennedy is a youngish-looking 37 with shoulder-length, dark- brown hair. His father, a corporate lawyer for General Electric, and his mother, were never particularly art-oriented. But that didn't stop him from moving toward his dreams. Lucy has a dark, mystical beauty with curly, long, black hair. She is Kennedy's right arm, doing make up and hair for his client's photos and catering to his many needs. She just spent a month in the hospital while Kennedy took care of their toddler, which, he said rolling his eyes with a smile, "was very trying, but fun. Needless to say it slowed down our progress, and I haven't gotten much work done." Kennedy would like to move from the high stress of commercial photography to the fine-arts end of it. He calls this his "personal work." One of his very sensitive photos taken near Cerrillos will appear on the cover of The Pinon Review, a natural and cultural history magazine soon to be published. "I'd like just my personal work to support us. That's a real big dream. An attainable dream, I think, but probably a couple of years off. So I'm still doing a little bit of commercial work," he said. Cerrillos and surrounding areas lend themselves wonderfully to Kennedy's commercial work. But it can be frustrating. "I just did a cover, one of the first ones shot out here, and there was some real strong stuff," he said. "Both the art director and I agreed that it was to be shot, and it was perfect. The musician, on the other hand, came out and said no, he wanted something else. It ended up that we did a shot of him just standing against a wall. It could've been done anywhere in the world." "Who's that?" I asked, searching for local stars. "Someone big-time,' he said mysteriously. He lit a cigarette. Kennedy avoids dropping names. David's and Lucy's house could be any post-hippie dwelling. Despite their lucrative past, they live in a humble adobe, typical New Mexico--- circa 1880 to 1980. Neo-unpretentious. The kitchen is ordinary with a counter, sink, the lived-in look-no incredible architectural features. The walls, of course, are decorated by his photos of Isaac Stern, Jesse, and two white cats; a Georgia O'Keefe print on the wall. Sophisticated music spilled out of the stereo in an undefined corner of the living room. "Who is that? Bach?" I asked. "Hmm...." He thought and smiled. "104.1 FM." There was a glimmer of 'real' stuff behind lively eyes. Photographing Bob Dylan was, curiously, composed of the same philosophy. "They're just normal people, you know," David said. "The thing that makes it successful for me is to approach them as I would you or me. They don't get treated very differently. Our studio in New York was not slick at all. I lived there, and the interior was all light wood, exposed brick and redwood. I built the place myself. It was similar to this place in Cerrillos. Sunny. Very unpretentious. I wore blue jeans, long hair, and my attitude was: If it's not good enough for you, don't come to my house." Kennedy treats everyone the same. He had Bob Dylan up on a ladder hanging props and making decisions. "Dylan loved it. I know how much Dylan hates photo sessions and just doesn't like the whole pretentious bull--thing. But when I went, I didn't take my assistant. He became my assistant. 'Listen,' I said, 'I gotta set up lights and hang paper, and could you give me a hand, man?' Hey, we were just two people who had something to do...." Kennedy laughed and tilted back in his chair. Lucy, still ill, managed to help David throughout the interview by making phone calls to delay appointments, reminding him of the time and bringing requested photos. Palladium, a sensitive, detailed process that takes a lot of time and knowledge, is now his favorite process for doing personal art. It's too time-consuming for commercial photos. One palladium, a beautiful photo of Lucy's nude torso three days before delivering Jesse, demonstrated Kennedy's superb technical skills and wonderful eye for design. Lucy looked tired. David looked concerned. "Don't you want to lie down?" he asked. "I want to support us and still live in Cerrillos," David said after she'd gone. "But trying to sell photos for themselves [versus commercial art] is a whole new thing for me. It's easy when somebody calls you up and says do this or that for $6,000 by such and such a date. But I got trapped into the business end of photography and payroll, contracts-and wasn't spending anytime doing photos." Kennedy received his first training at the New York Institute of Photography when he was seventeen. A few years later he attended Brooks Institute in Santa Barbara where he got most of his technical training. But the real learning was when he assisted people like Rudy Legname, George Housman and Klaus Lucks. His intention was to leave New York City as soon as possible and return to his native Northern California or somewhere saner. During those years he built up an excellent reputation in the record industry. As soon as his back problems were corrected, however, Lucy and he began looking for better places to live. Two places intrigued them: Jackson Hole, Wyo., and Cerrillos, N.M. Of course, Cerrillos won, because as Lucy said, "There were only two art galleries in Jackson Hole." And there's Santa Fe and Taos's strong art markets, the airport in Albuquerque and reasonably close color separators and printers. So the decision became final. "I've made some attempts to contact ad agencies in Albuquerque, but I find them strange," he told me. "Why?" I asked. He didn't answer immediately, a man as careful with words as his images. "The money is ridiculous, for one. I mean, big money isn't important if it's some thing I like, but the stresses of commercial of demand it. Also, when I got here I wasn't expecting trumpets, but I expected a little bit of interest. I went in with a relatively heavy book-portraits of Dylan and Springsteen. I mean, in New York, I was not a major, major heavy-weight, but I was a contender. I'd be told in Albuquerque, 'What type of awards are these? If you haven't gotten any local awards, you're a nobody...." On Kennedy's office wall are 10 or 15 awards, among them several "One-Show Merit Awards," several "Creativity-Art Direction Awards," at least seven "Art Director Club Awards," all spanning over the last ten years. I mean, I didn't expect people to fall over me, but I felt the same as when I went into New York ad agencies when I first started ..…" There was a boyishness, better, an innocence suddenly to his face. But local commercial photography doesn't concern Kennedy now. After all, he still has plenty of connections in New York, and his real interest is to become better-known for his photos as art. Our time ended. He walked me to my Ford. The day was a perfect New Mexico winter day. The sky was painfully blue. The tape recorder off. A softness of having completed something surrounded Kennedy's kindly farewell. "It's odd," he confided. "I'm not sure what to do with just taking photos. What do I do with them? Who'd want them?" I laughed. I couldn't help thinking: Isn't that every artist's plight? There's a trade-off moving toward sanity.