January 15, 1986

Press Articles :: Photo Design Magazine

|

|

|||||||

|

"I went to Brooks Institute in Santa Barbara for a year and a half," Kennedy continues. "The goal of Brooks was to develop commercially successful photographers. I wanted to learn technology, not S-curve composition. To me, technology is what a school can teach you. I didn't want someone to tell me what good composition was. I figured if I didn't intuitively feel it then the rest of my life would be spent constantly thinking, 'If I put that over there then that will be the top of the S. If I put that over there that will balance the other half.'.What I wanted was to master technical things in order to make them do what I wanted. You can develop vision in someone but I don't agree that you can teach creativity". "I think the best photography is intuitive," says Kennedy. "My wife Lucy doesn't work in technical terms. She has no idea of cameras, f-stops. But, I wish some of my pictures were as beautiful as hers. Her intuition is fantastic. I'm always calling her in and asking, 'Is this good? What do you think? Did I do good? Is this the right one, Lucy?' She's probably my best editor. She does hair and make-up for me and keeps the studio functioning. I couldn't do it without her." Once out of Brooks, Kennedy moved up to northern California, settling in a small town on the California/Oregon border for the next two years. "I opened a little photography studio in a place called WACO," he elaborates, "Western Artists' Cooperative. We had a huge 40,000- foot warehouse right on the bay where I began shooting a lot of nature in addition to portraits. But, I had back trouble and none of the doctors in California seemed to know what the problem was. So I came back to New York at 22 to have surgery, figuring I'd go back to California after about six months. That was in 1973. I'm still here."

"When I got out of the hospital," Kennedy remembers, "I planned on freelancing as an assistant. The level of what I was doing in California was not real high. I was doing some good pictures and having a lot of fun. But looking back, I was still really a beginner. So, I started working for a few people and ended up getting a full-time job for a still-life photographer, Rudy Legname. I worked for him for about a year and a half and learned an incredible amount about lighting technique. He was an exquisite photographer. I love his work and it was good for me because it was still-life. When I left Rudy I was able, through his training, to start my own studio. I began with one Nikon and one lens. But, I was truly lucky when I left him because I had made good relations with all my suppliers. So, when I opened my own place, I had wonderful credit and a lot of people behind me." For a year or year and a half Kennedy tested, moving towards fashion, which he feels is the most accessible outlet for a young photographer. "But, I really couldn't plug into the fashion industry," he recalls. "I was from the country and fashion and I just didn't connect." At the same time, Kennedy began to hit the advertising agencies, acquiring quite a bit of work from Benton and Bowles including Charmin toilet tissue and Dawn dishwashing liquid assignments. "All this time I didn't have a rep," says Kennedy. "It was just word of mouth and me seeing people. Then an art director who I had worked with at B&B went to CBS advertising. She used me on her first job there. Within a couple of weeks I was working for seven or eight designers in the CBS ad department. A month or two later I was working for all of them. So it snowballed. I was getting great stuff. One assignment called for a picture of a tree and I was able to go up to Woodstock for two days just to photograph nature. I was doing what I really loved. Yet, I made the mistake that many photographers make - one client. When they cut all the budgets at CBS I was out in the cold. I had a few small jobs in the works but nothing mainstream. Kennedy decided to target the record industry with full force hoping to do the kind of photography that he thoroughly enjoyed. He wanted to do album covers but it was difficult to make the transition from working for an ad department to producing covers. "I sat for a while trying to figure out what to do and ended up starting a portrait project of the top album-cover art directors in New York' he explains. he explains. "I called them and asked if they would come down to my studio to be photographed. Everyone knew what I was doing. I was looking for jobs. But, enough people had seen my work and I was straightforward enough in my approach that they all agreed. They could see my space, witness how I work, get to work with me and about a week later they received a small print." The strategy paid off. Within approximately six months Kennedy was shooting album covers and his business flourished. "David came up with this great scam to break into the record business," says former CBS art director John Berg. "He was going to do this giant article on record-cover designers and got a lot of people to come down and sit for portraits. He tried me and I finally did it. It's true, he did dress me in his shirt and his jeans but it was a great portrait. I started using him and I discovered that he is extremely adaptable. David can do anything. To find a photographer who can really cover everything, and if he doesn't know how to do it will learn, is spectacular. He became my personal photographer at CBS." "I always liked the larger formats," Kennedy adds of his affinity for covers. "I never liked 35. 1 started shooting 4x5 and 21/4 in California and always related to the square. So, album covers were a natural." After a second bout with back surgery in the fall of '83 and a year-and-a-half hiatus in his career, Kennedy became increasingly involved in the advertising community. Working with a rep named Chris Conroy, he attracted a wide variety of accounts.

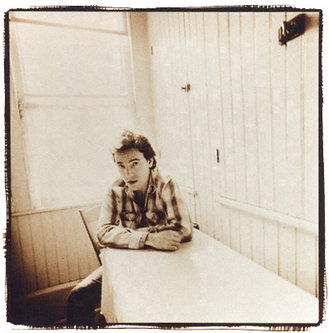

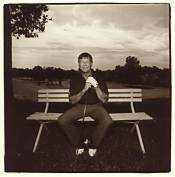

Lively verbal interaction marks most of Kennedy's portrait sessions. In the few instances when he finds it difficult to communicate with a subject on a personal level, he may choose to focus on a graphic formalism, "one interesting aspect of them." Because even when people are not willing to relax or spend the time there are what he describes as, "little instants, seconds when they let go of something. It's just a matter of watching and grabbing it. But, there's no plan like 32b. There's no predetermined way to solve the problem. If you focus in on what you're doing and look very intensely you'll see a little bit of light in the tunnel." Spending as much time as he has photographing people, Kennedy still claims that he will never be capable of thoroughly understanding them. Their nature remains fascinating and alluring. "I think that's the main reason I love photographing people," he admits, "because I'm so amazed by them. There are a lot of photographers who shoot people and there are so many diverse approaches. I try and find the best in a person." At ease with his sitters whether they be celebrities of the music world, rock-and-roll idols, politicians or scientists, Kennedy strives to recognize as well as accommodate their singular and individual needs. When he discovered that he had been selected to execute all the public relations material for Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska album - by virtue of a seven-year-old photograph he had taken out his van window in Nebraska during a trip across country - he was insightful enough to grasp Springsteen's motivation. With the Nebraska picture already accepted as the album cover, Kennedy decided to

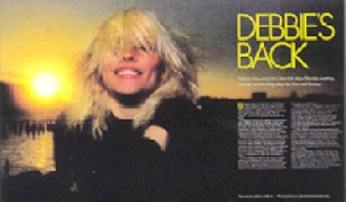

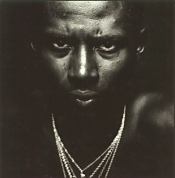

utilize his own parents' summer house as the locale for a formal shooting session. The large, funky house, enveloped in weathered wood, filled with early American antiques and engulfed by 40 acres of untarnished land, proved the ideal visual supplement to Springsteen's own aesthetic. "We spent a day wandering around the house and the woods," comments Kennedy, "and had a great time." "Dylan." Kennedy utters the name as his facial features brighten. "Dylan was terrific to photograph," he says. "I was nervous. In the last couple of years he's probably one of the few people who really made me nervous about a shooting. When that job came up through Spin magazine, I was in heaven. I didn't hire any assistants. I knew that Dylan didn't like to be photographed and also had the impression that he would not appreciate a slick attitude. I figured that it made a lot more sense to approach it one on one. Unfortunately, that got me a little crazy because I had to take sole responsibility for everything on the shoot. But, I thought that the two of us alone would be more comfortable and work better. As it turned out he started helping me tack seamless up and arrange things. He really got involved in my end of the process. I grew up on Bob Dylan. I think I was a bit afraid that I was going to meet him and he wasn't going to be everything that we all thought he was. It was so wonderful because he was so friendly, so nice, helpful and very right on the money." Involved with Spin even prior to its inception, Kennedy met Bob Guccione, Jr., the magazine's editor, publisher, and design director, through his working relationship with Omni and Penthouse. "I've photographed some interesting people for Penthouse," he states, "George Carlin, Michael Jackson. So, through my association with his father, Bobby came to see me at the studio and we pulled out pictures for his dummy issue of Spin. He used a bunch of them and I've been photographing for him ever since. He's one of my favorite clients." "All of my editorial clients are, of course, my favorites because I get to read the article and I get creative freedom," Kennedy continues. "The range is so wide. In the last year I shot Senator Lowell Weicker from Connecticut, Mark Breland, and Dr. Jorge Yunis, the Minneapolis geneticist who researches the relationship between DNA and cancer. I did a portrait of a woman living in California who is a Soviet Union psychic. Apparently, Russia is far ahead of us in psychic research for warfare.

"One of the things that distinguished Spin magazine from the beginning is that we really went for great photography," says editorial client Bob Guccione. "David and I became friends a long time ago when I was putting out a poster magazine. He showed me his book and I saw that his work was much too good for what I was doing, which was a teen-oriented magazine. But, I hoped one day we'd work together. When I started Spin, before I even had the magazine, I was trying to work on a dummy. I went around to David's studio thinking I'd borrow some art work and I told him that I couldn't afford to pay him. He said that was no problem and I told him that one day it would all work out. Now he's our top photographer and we assign him more work than anyone. If you look at the magazine there may be more credits to people who have a vast stock library. Some photographers have been published more than David. But, David's our first choice whenever we do assignments." "I think the best thing that really epitomizes our relationships," continues Guccione, "is that we really stuck by each other through hard times. When I first went to him it was my hard time and he stuck with me. And then, when he was having a hard time after his back surgery, we were trying like mad to get photo jobs for him. We know each of us is there for the other and we respect each other. He's a real artist."

An abundance of enthusiasm seems to be Kennedy's secret in juggling all the various aspects of his photographic career. John Berg describes this quality as an "energy that is unique. He brings it to a job, overcoming problems and resolving horrendous situations. You would avoid trying to do the picture if you had to use another photographer. But, you can go to David and he will solve it beautifully. He takes on everything as a challenge. He's a world beater." "He did Major Thinkers for me on Avenue A or B," Berg continues, "somewhere down there in Alphabet City. Those people will kill you. Well, David had a van and, in the back, a giant dog the size of a horse. The terror of that dog kept everyone away from us and from running in front of the camera. They finally started throwing things after a few hours but we got the job done because he thought to bring the dog." Kennedy sniffles at the reminiscence and describes his method of working with great vigor. "I'll say, 'Put the camera down there,' and nine times out of ten if I move the camera after that I'm in trouble," he explains. "This is right. It feels good. That's where we're going to do it. But, then I'll look through it, shoot and think, 'Well, maybe if I move a little to the left.' You don't have to move. The minute you do you open yourself up to a whole new set of problems. It's a gut thing. I hate to say it's like Zen but you really do feel it."

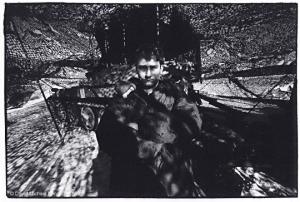

"I never stop until I'm absolutely certain," Kennedy adds. "Sometimes it's two or three runs, sometimes 20. Once you've got it, you've got it. Because most people don't like to be photographed, why put them through any more discomfort than you have to. If you're relaxed with what you're doing as a photographer you know you've got it." Not choosing to "clutter" his pictures, Kennedy rarely utilizes props in his photographs. "When I go on location and I'm in somebody's house, the whole house is a prop," he says. "My painted canvas backdrop in the studio is a prop. But, a prop that just gives someone something to do usually confuses people. The simpler the better. Sometimes a prop works because it says something about the person. And, sometimes a prop is necessary." "Once I had to use 22,000 screw-gun nails, two tons of potatoes and two crews of six assistants to create a room lined with potatoes for this particular Devo shoot for Penthouse," Kennedy divulges. "I got the idea because the group is sometimes known as the Spud Heads or the Potato Heads. It was a bit of a complicated session because we couldn't put the potatoes up in advance or they'd fall off. So, we had one crew in who built a plywood room which telescoped down so the front opening was 12xl2 and the back opening was 3x5. We built it the morning before the shooting. During the next 15 to 20 hours, up until the session, the first crew screwed in all the nails while the second sliced potatoes in half, jamming them onto the nails so they'd stay on the heads. As it was, we shot for about two-and-a-half hours using a little bit of dry ice for a fog effect. After about two hours the potatoes began falling off." So much for minimal propping. "Probably my single most failing grace in the industry," Kennedy admits with a certain register of regret, "is that I'm the worst salesman of my own work. I can do it if I have to but I'm a terrible businessman. I've never advertised in books. I really should. I've been doing platinum prints for approximately six months and have 15 or 20 of them in the studio. They should be put together and shopped around to galleries but I don't feel I have the head to do it. Once it's done and I love it, it's done and I go on to the next thing. Right now I'm working on a possible show of the Department of Defense photographs at The National Gallery in Washington D.C. I'm planning on printing them 30x40 or larger and am absolutely thrilled at the prospect of the exhibition. "I don't attempt to draw a line between my personal work and my commercial work," Kennedy confides. "it seems to me that the commercial work gets so involved and takes so much out of you that it would be very difficult for me to "work" all day and then ever take pictures for myself. I really want to keep the two much closer together. It's nice to go out on jobs feeling that they are not just for the money, not simply fulfilling an art director's need. "I adore photography," Kennedy concludes. "occasionally, I begin to feel it's almost too much a part of my life. I start feeling guilty becouse I'm not spending enough time with my son." Then I get him in front of the camera and we make photographs. It will always be my main thrust. Photographers that are really good really love it. It's something you have to dedicate to because your constantly proving to yourself that your as good as your last shot. That's an old saying that is true. I'll always stay in the medium but I'm constantly changing directions. One week I'm in Germany photographing soldiers. The next week in Malibu photographing Dylan. That's why I love it so much. You never know." The humanism of the man, the sensitivity of the photographer-an artist mirror image. _____________________________________________________________________ Emily Simson is a New York based Freelance writer recently named an associate editor of Photo/Design

|

photographer to formulate judgments of value. By virtue of conscious structural decisions - camera placement, depth of field and positioning of the subject - stereotypes as well as connotations may be reinforced or minimized. By embellishing (or sublimating) their evocative power through techniques of lighting, exposure and printing, the photographer may markedly heighten the emotive impact of his intended message. The resultant image, in essence, can never reveal a veritable "reality" but only one man's humanism - one artist's truth revelation, "Every step in the process of making a photograph is preceded by a conscious decision which depends on the man in back of the camera and the qualities that go to make up that man, his taste, to say nothing of his philosophy," wrote Berenice Abbott in 1964. "The portrait is your mirror," German portraitist August Sander stated succinctly. "It's YOU."

photographer to formulate judgments of value. By virtue of conscious structural decisions - camera placement, depth of field and positioning of the subject - stereotypes as well as connotations may be reinforced or minimized. By embellishing (or sublimating) their evocative power through techniques of lighting, exposure and printing, the photographer may markedly heighten the emotive impact of his intended message. The resultant image, in essence, can never reveal a veritable "reality" but only one man's humanism - one artist's truth revelation, "Every step in the process of making a photograph is preceded by a conscious decision which depends on the man in back of the camera and the qualities that go to make up that man, his taste, to say nothing of his philosophy," wrote Berenice Abbott in 1964. "The portrait is your mirror," German portraitist August Sander stated succinctly. "It's YOU."

Mark Breland

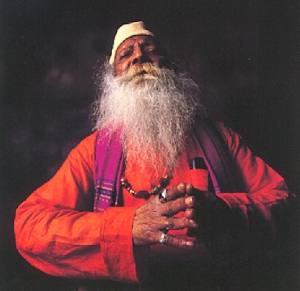

Mark Breland They're very very into it. We spent a day with her, ended up in the Berkeley hills at a fire walk and photographed that. Then we went down south and worked with another Soviet psychic who's working on the same type of thing. So, the range of people and ideas is just phenomenal."

They're very very into it. We spent a day with her, ended up in the Berkeley hills at a fire walk and photographed that. Then we went down south and worked with another Soviet psychic who's working on the same type of thing. So, the range of people and ideas is just phenomenal."